Every now and then films appear where the Jungian references are so clear that one is almost certain that the directors know their Jung. Reviewed by Steven Walker, Professor of Comparative Literature.

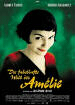

AMELIE

Reviewed by Steven Walker

Professor of Comparative Literature

Rutgers University

Author of Jung and the Jungians on Myth

(2nd edition paperback by Routledge in 2002)

Every now and then films appear where the Jungian references are so clear that one is almost certain that the directors know their Jung. This is the case with the new French hit Amelie (directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet), wildly popular in France, and one of the most popular French films to be distributed in the U.S. in a long time. But what is the film's special interest for Jungians? It is found in the words "an introverted young woman can wreck her own life'-words that formulate a timely warning for Amelie at a crucial turning point in the film. Amelie (played by the kittenish Audrey Tautou) works in a café-restaurant during the day and then goes back to spend the night by herself in a little apartment in Montmartre. She has, to all appearances, a nice introverted life, and she seems happy with it. Why should we worry about her? After all, Jungian psychology has always defended the introverted life and its values against cultural prejudices favoring mindless extroversion. But can there be too much of good thing? Is the introverted response always the proper response for an introvert? The film offers a balanced perspective on this issue; I guarantee that introverts will not feel offended.

Every now and then films appear where the Jungian references are so clear that one is almost certain that the directors know their Jung. This is the case with the new French hit Amelie (directed by Jean-Pierre Jeunet), wildly popular in France, and one of the most popular French films to be distributed in the U.S. in a long time. But what is the film's special interest for Jungians? It is found in the words "an introverted young woman can wreck her own life'-words that formulate a timely warning for Amelie at a crucial turning point in the film. Amelie (played by the kittenish Audrey Tautou) works in a café-restaurant during the day and then goes back to spend the night by herself in a little apartment in Montmartre. She has, to all appearances, a nice introverted life, and she seems happy with it. Why should we worry about her? After all, Jungian psychology has always defended the introverted life and its values against cultural prejudices favoring mindless extroversion. But can there be too much of good thing? Is the introverted response always the proper response for an introvert? The film offers a balanced perspective on this issue; I guarantee that introverts will not feel offended. The terms "extroversion" and "introversion" have been part of our general vocabulary for a long time, and using them implies no particular knowledge of Jungian psychology; in fact, they were probably the first piece of Jungian vocabulary to cross over into ordinary English usage, long before "archetypal" started to mean (improperly) "typical" a few years ago. But the corresponding French adjective "introvertie" is used less frequently, so I think that in this case one can maintain that the director Jean-Pierre Jeunet has used it in a specifically Jungian sense. Ameilie, as "une jeune fille introvertie," is a genuinely Jungian character - at least in this French film.

The film's warning that "an introverted young woman can wreck her own life" is especially timely for Amelie, because she is teetering on the edge of what Erik Erikson called the major life crisis of youth: the struggle to achieve intimacy and to avoid being stuck in isolation. Amelie is, in fact, beginning to show signs of dissatisfaction with her isolated life: no friends but her coworkers, and nobody to spend time with on weekends but her emotionally distant father, who is self-absorbed and hardly listens to what she says on her visits to him. She clearly needs help - if not a therapist's help, at least a mentor's help in successfully negotiating this life transition from isolation to intimacy. (Interestingly enough, as regards her need for mentoring, the French title of the film - Le fabuleux destin d'Amelie Poulain/The Fabulous Fate of Amelie Poulain - gives Amelie a last name that is quite appropriate and inspiring for a young girl trying to get help in getting a life: "poulain" means literally a young horse, but it can also mean a young person who is getting a leg up in business thanks to a mentor's support.)

The mentor who helps her turns out to be an old man living across the courtyard in her apartment building. He is himself very much of an introverted recluse. He never leaves his apartment, but keeps himself occupied by painting a detailed and full scale copy of Renoir's famous celebration of extroverted social life "Luncheon of the Boating Party." The old recluse is almost finished with his copy, but he is baffled by the final task of painting the facial expression of a young woman who is leaning over towards the viewer in the foreground of Renoir's painting. He is trying to put this finishing touch on the painting when Amelie comes into his life, the very embodiment of the woman in the painting, since she also needs, so to speak, a "finishing touch."

Copying Renoir's happy extroverted painting is not only a compensatory activity for the old introverted recluse; the painting also has a message for the overly introverted Amelie, since it is clear that its evocation of the whirl of happy young couples contrasts vividly with the image of Amelie's lonely apartment in Montmartre. Actually, it is not really fair to call her apartment lonely, since introverted Amelie actually seems content with making meals for herself, occasionally chatting with her downstair's neighbours, and discovering sex but not finding it worth the trouble of pursuing it further and building a relationship. At the opening of the film, it seems that her life by herself suits her fine - but does she really have a life? That is the question.

As though to answer this question the film gradually has Amelie edging towards engaging herself more with the outside world. Up until this point she has been an amused observer of other people's lives and foibles; she would rather observe or imagine their lives than get on with her own life. At the opening of the film she is imagining, as she looks down at the view of Paris from the hilltop of Montmartre, how many couples are having orgasms in the city at that very moment ("fifteen," she concludes with a smile, and we see all fifteen as she imagines them in an amazing fifteen second sequence). But now she begins to actively intervene in other people's lives, at first in some strangely distanced ways. For example, after discovering in her apartment a tin box in which years before a boy had hidden his personal mementos and treasures, she goes through an elaborate search to find the grown man who as a boy had left this trace of his life in what later became her apartment. When she has found him, and has returned the box without his knowing who returned it, she watches him from a distance as he almost weeps over the inexplicable appearance of this lost object from his lost youth. In another attempt to participate more actively in the life of people around her, she deliberately spills coffee on a coworker, which obliges her friend to clean herself up in the restaurant's restroom where the man she has been lusting after has gone a moment before. But soon Amelie is involved with her own game of sexual pursuit and, keeping her identity a secret, is spying on a shy young man (played by Mathieu Kassovitz, the director of the remarkable 1995 film Hate), who, although he works in a sex shop, is as introvertedly at a distance from extroverted engagement with life as she is.

A perfect match for her, n'est-ce pas? But the question remains whether Amelie can step out of her introverted life style long enough to solve the Eriksonian youth crisis of isolation vs. intimacy. Fortunately, all it takes is a mysterious warning ("an introverted young woman can wreck her life," remember?) from the artistic recluse downstairs for her to realize that it is finally time for her to take action. But will she take action? Of course she will: this is a French feel good movie! So Amelie Poulain is off and running, and viewers will cheer at the end of the film as this introverted young woman demonstrates that she can also act like a real extrovert when the situation calls for it. See the film and find out how she does it!

© 2001 By Steven Walker.

Contact Steven Walker: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. or This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

{/viewonly}